Former Kailua dentist Lilly Geyer sank her head into her arms and wept Friday after a Circuit Court jury found her not guilty on all counts in the death of her patient, 3-year-old Finley Boyle.

Minutes later she leaned over the railing to hug and kiss her son and daughter. Her daughter is the same age — 8— that Boyle would have been today if she had survived. Boyle’s father, Evan, and grandfather Joseph Boyle were seated just a few feet away.

Finley Boyle stopped breathing and suffered cardiac arrest in the dentist’s chair after being sedated on Dec. 3, 2013, as Geyer was starting to perform a baby root canal at Island Dentistry for Children. The little girl suffered massive brain damage and never regained full consciousness. She died Jan. 3, 2014.

The jury deliberated 3-1/2 days before acquitting Geyer of charges of reckless manslaughter, second-degree assault and “manslaughter by omission” for failing to get medical aid promptly.

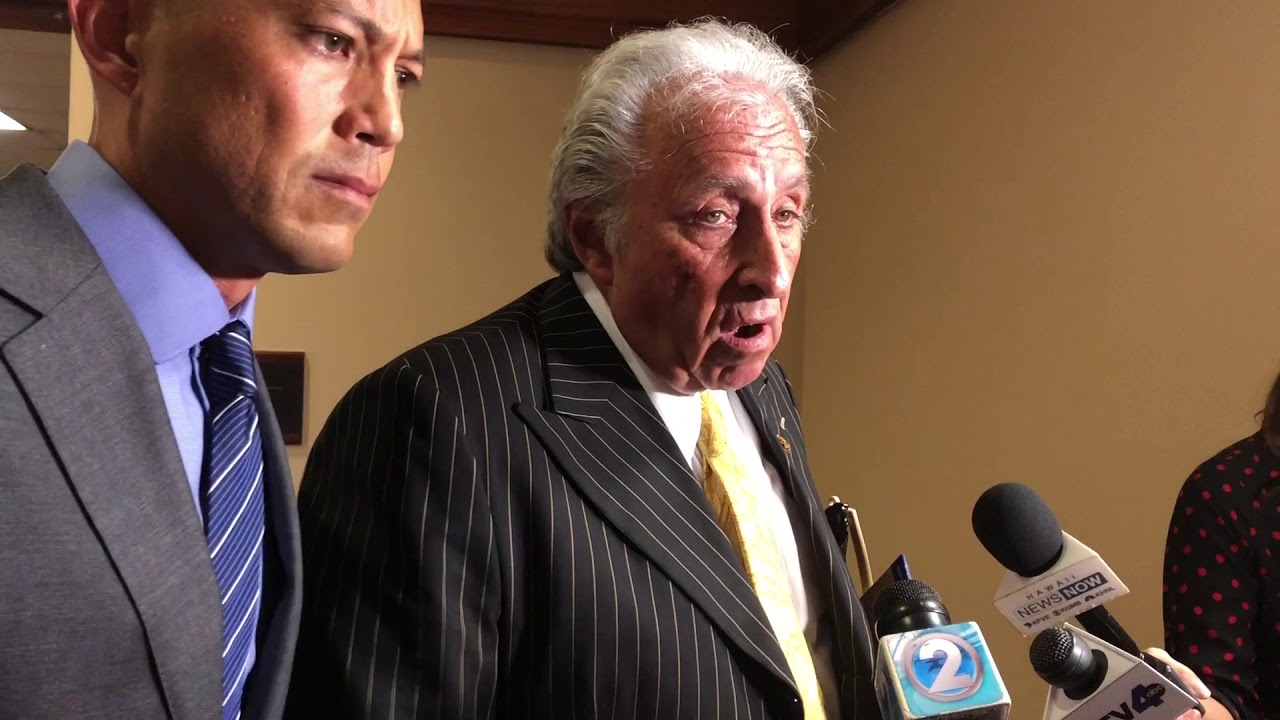

“It’s not a day to celebrate, and our hearts go out to Finley Boyle and her family,” said defense attorney Thomas Otake. “We are relieved, obviously. Our position all along was this should have never been a criminal case.

“To charge a doctor or dentist with a crime when things go wrong in health care, that’s just not good for our community. And it was based off of a lot of mistaken beliefs on the part of the attorney general. … This child was not overdosed.”

Boyle’s mother, Ashley Puleo, tears streaming down her face, declined to comment after the jury rendered its verdict, but Boyle’s grandfather later spoke to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser.

“The entire Boyle family is extremely disappointed in the verdict,” he said. “The pediatric toxicologist that the prosecution brought from California said that Finley Boyle died from drug toxicity. It’s the combination of five drugs that were given to her. The Boyle family will always believe that is what caused her death.”

At trial before Circuit Judge Paul Wong, Deputy Attorney General Michael Parrish argued that the sedatives the girl received were too strong in combination and that the dentist didn’t do enough to save the child.

The state faulted the dentist for not being present in the office when an assistant sedated the child and for failing to perform CPR. They also pointed to a delay of 13 minutes or more before anyone called 911.

Geyer testified the dosage was appropriate and that she did everything she could to save the child. She also said she told one of her assistants to call 911.

The defense argued that a laryngospasm, or spasm of the vocal cords, blocked Boyle’s airway and was a lingering effect from an upper respiratory infection diagnosed nearly a month before the dental procedure. That diagnosis came the same day, Nov. 7, 2013, as Boyle’s first dental visit, but her mother did not disclose it to Geyer.

Attorney Michael Green chastised Boyle’s mother for not disclosing the diagnosis to the dentist that day, saying that laryngyospasm can occur four to six weeks later.

“If she would have told the truth, nobody’s here today, because my client’s not going to do the sedation,” he said.

At that first visit, Geyer concluded that the child needed four baby root canals and fillings for cavities, and scheduled the procedure for Dec. 3.

Puleo, who is a nurse, said she was surprised because her daughter had not complained of any pain in her mouth.

According to the autopsy report, Boyle received 31.03 mg of demerol, 10.34 mg of hydroxyzine and 824 mg of chlorohydrate. The drugs were given by an assistant because Geyer was late to the office. After Geyer arrived, Boyle also received nitrous oxide, also known as laughing gas, and lidocaine with epinephrine as a local anesthetic. Boyle weighed 38 pounds at the time.

“Immediately following the lidocaine injection, the decedent became unresponsive and went into cardiopulmonary arrest,” medical examiner Dr. Christopher Happy wrote in the autopsy report. He listed the cause of death as “infectious complications following cardiopulmonary arrest during dental procedure,” and described the manner of death as an accident.

Green said the case would have set a dangerous precedent if the dentist had been convicted, opening the door to criminal prosecution for nurses, doctors and health care providers when patients die, rather than civil claims for medical malpractice.

Geyer shut down her practice after the event, and Green said after the verdict, “She’ll never practice again.”

“The Boyles would like that in writing,” Joseph Boyle responded. “Because when you let your receptionist drug your patients, when you are not even on the premises, you have minimally violated a professional duty to your patients that should result in your license being sanctioned.”

He said the dentist had a duty to check on the child’s health on the day of the procedure as part of a “systems review” but was not in the office when she was sedated. He also questioned whether Boyle even had dental disease, noting that the autopsy found that her teeth were in good shape.

Boyle’s parents filed a lawsuit against Geyer for negligence in her treatment of their daughter and reached a confidential settlement out of court.

Asked whether Geyer had surrendered her license, Green said the next step is for her to go before the licensing board, which will decide whether to revoke it.