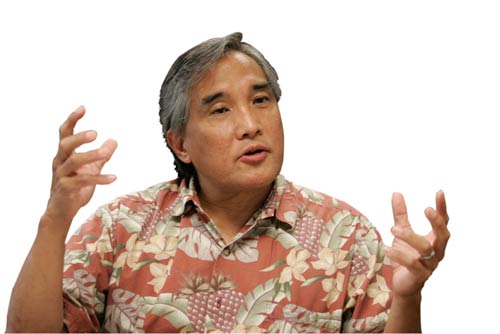

Physician touts prevention

Dr. Neal Palafox would promote healthy lifestyles to counter a costly, broken health care system.

“We have a truckload of evidence … that the current health care system costs way too much and doesn’t work. People have to understand how their roles affect health outcomes.”

Dr. Neal Palafox

Newly appointed director of the state Health Department

With its economy sputtering, Hawaii is in the perfect position to foster healthier residents at less cost, says Health Director-designate Dr. Neal Palafox.

Dr. Neal Palafox » Age: 58 |

"Real change happens when you hit rock bottom," Palafox said. "With everybody worried about their bottom line, now is the time for everyone to come together. The lack of dollars can help us rethink how we do things so we can spend less on health care and get far better results, which is good for business and good for people’s health, that’s for sure."

The key is to bring together the heads of Hawaii’s hospitals, health insurers, government leaders — and especially ethnic, religious and geographic communities — to reconsider how people deliver and receive health care in the islands, Palafox said.

He advocates focusing on preventive steps and healthy lifestyles over better access to doctors and hospitals.

"Health care is extremely expensive and the returns are terrible," Palafox said in an interview in his third-floor office at the state Health Department on Punchbowl Street. "We have a truckload of evidence … that the current health care system costs way too much and doesn’t work. People have to understand how their roles affect health outcomes."

As chairman of the department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the University of Hawaii’s John A. Burns School of Medicine, Palafox, 58, has been teaching doctors in training that hospitals, physicians and medicines have far less effect on patients’ health than other factors such as income, education and housing.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

It was a lesson that Palafox saw firsthand over nine years in the Marshall Islands, where he started as a newly trained doctor out of UCLA in 1983 and became the republic’s medical director.

While Palafox sometimes treated 115 patients per day, more powerful factors such as overcrowding and poor housing conditions continued to help spread tuberculosis and Hansen’s disease, he noted.

He argues that the heads of critical state agencies, such as taxation, labor, economic development and education, should consider the health needs of people when making broad decisions.

For instance, Palafox wants education officials to think about the long-term health effects on children as they deliberate whether to close a school to save money.

Palafox, in turn, would consider other departments’ strategic goals in making decisions at the Health Department, he said.

"If you’re stuck in an old model, you’ll never be creative," Palafox said. "If you’re forced to think differently, that creativity will launch you into patterns we haven’t even considered, especially when it involves the health of our community."

HIS APPOINTMENT, which is subject to confirmation by the state Senate, has been praised by leaders in the health care community.

"The Queen’s Medical Center has enjoyed a very positive and productive working relationship with the state Department of Health and believes this strong relationship will continue to grow and develop under Dr. Palafox’s leadership," Art Ushijima, president of the Queen’s Medical Center, said in a statement.

Dr. Lee Buenconsejo-Lum, an associate professor in Palafox’s department of Family Medicine and Community Health, met him 17 years ago as a student and has worked with him in several different capacities since.

"His whole life’s work has been about reducing health disparities and getting priorities more focused on prevention," Buenconsejo-Lum said. "It’s not just talk with him. He has worked with ministers, directors and policymakers from various diverse communities to bring them all to the same table to work toward shared visions from diverse partners with sometimes conflicting opinions."

Palafox helps produce positive results by being a good listener, Buenconsejo-Lum said.

"He is calm and rarely gets flustered, even in the most contentious situations," she said. "He always tries to find the positive in every situation, and he asks these really good, out-of-the box questions in a very nonthreatening way that really makes people think differently."

As a boy, Palafox learned that he liked science by helping his father, Anastacio, develop UH’s poultry science department.

Palafox helped gauge the effects of nutrition and biochemistry on chicken eggs and used a micrometer to help find the perfect thickness of eggshells, which had to be stout enough to withstand the rigors of an egg factory while still being easy to crack open.

When he was in the eighth grade, Palafox and one of his brothers were recruited by a teacher to assist with swim therapy for Easter Seals clients because the Palafox boys were surfers and good swimmers.

"We thought we would work with handicapped children and adults at the Y and be done after a day or two," Palafox said. "I went and kept going back."

Palafox later became an Eagle Scout and realized that he loved science and helping people.

He was one of the first to enroll in Imi Ho’ola, UH’s post-baccalaureate program designed to help prepare students from disadvantaged backgrounds for medical school.

The program led to a degree from UH’s medical school, residency at UCLA and a master’s degree in public health from Johns Hopkins University.

Palafox had no particular specialty in mind when he set off on a career in medicine.

"Whatever I did, I knew it wasn’t going to be about me," he said. "I just wanted to affect other peoples’ well-being."

Palafox has been told repeatedly that the job of health director can be time-consuming and tough, "but I’d rather take the challenge and dive in," he said. "It doesn’t make sense to do nothing and wait."