Translations of letters written by the earliest Hawaiian Hansen’s disease patients exiled to Molokai in the late 1800s paint a much different picture of early life in the settlement than the brutal image perpetuated by English-speaking, mostly Caucasian authorities at the time.

"The perception has always been that everybody there was immoral and lawless," said Anwei Skinsnes Law, who has been studying the history of the Kalaupapa peninsula for 40 years. "Letters from administrators said they were vagabonds and murderers. When you include the voices of the people who were actually sent there, it tells a much different story. When you just don’t rely on English sources, the history becomes much more complete."

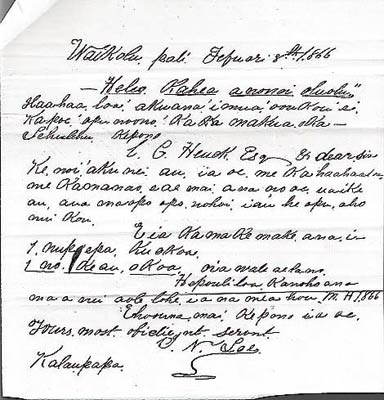

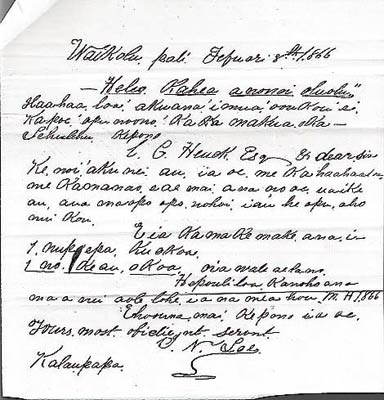

Hawaiians are often portrayed as relying on an oral history. But in the 21st century it’s the written words of the first Hawaiian Hansen’s disease patients, on file in the Hawaii State Archives, that offer a different perspective of life in Kalaupapa than the one perpetuated through movies and books.

KALAUPAPA WORKSHOPS

To discuss Anwei Skins nes Law’s research:

>> Maui Arts & Cultural Center: 10 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Sept. 22

>> Iolani Palace: 5 to 8 p.m. Sept. 25 and 5 to 8 p.m. Oct. 2

>> To register: Email info@kalaupapaohana.org or call 573-2746.

|

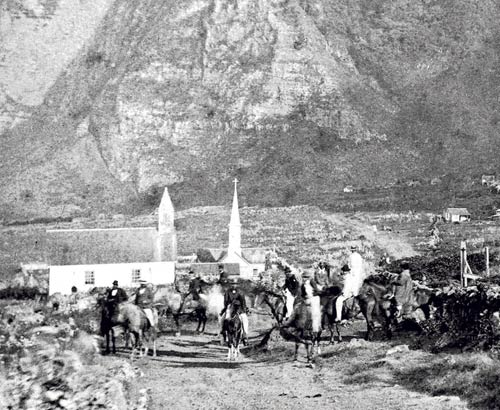

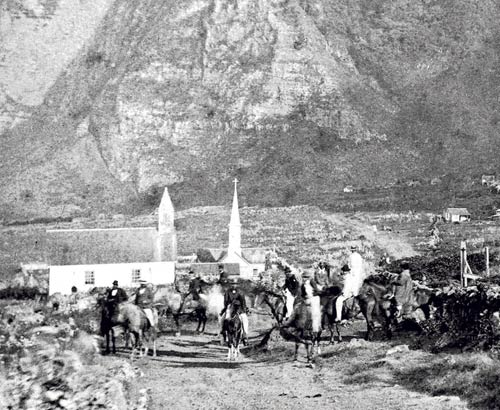

According to popular lore, the first patients sent to Kalaupapa on Jan. 6, 1866, were forced out of boats and left to swim ashore to rocky, unfriendly terrain where they had to fend for themselves.

But Law has been unable to find any evidence backing up that scenario.

On the contrary, Law said, the letters from patients suggest that Hawaiians who were in Kalaupapa before the arrival of the Hansen’s disease patients not only stayed, but also helped the patients adapt to their new home.

Some patients wrote to the Board of Health requesting calabash bowls and poi bowls, perhaps to replace those that they borrowed from their benefactors, Law said.

J.N. Loe, one of the first Hansen’s disease patients to arrive, wrote to the head of the health board asking for a newspaper to be delivered by boat, Law said.

"He wasn’t asking for food," Law said by telephone. "When you think of the traditional image of Kalaupapa, what does it say that one of the first letters from Kalaupapa is to ask for a newspaper?"

And within six months, as the number of patients grew, 35 of them organized a congregation that would eventually become St. Philomena Catholic Church in Kalawao, where Father Damien’s later work with Hansen’s disease patients led to his ascension to sainthood.

Even before the church’s building was erected, the first patients kept 300 pages of church minutes that Law discovered in the archives.

"The disease has always been written about in a way that promotes a stigma and promotes shame and promotes fear," Law said. "But they not only organized a church, they kept minutes of their first meetings."

Law’s research is the basis for her new book, "Kalaupapa: A Collective Memory," published this month by the University of Hawai‘i Press.

Since 1994, Law has been the international coordinator of the International Association for Integration, Dignity and Economic Advancement, based in Seneca Falls, N.Y. It is described as a human rights organization for people who have experienced leprosy.

Law first went to Kalaupapa at the age of 16 to accompany her father, Olaf Skinsnes, a University of Hawaii professor who studied Hansen’s disease around the world.

But it wasn’t until eight years ago that Law turned to the Hawaiian-language documents stored in the state archives.

After having dozens of documents translated into English, Law isn’t even certain how many more documents remain that will continue to tell a modern generation of Hawaii residents about 19th-century life in Kalaupapa.

"I think we’re only seeing the tip of the iceberg," she said.

The translations do not detract from the noble work of Saint Damien or Mother Marianne Cope, who will become Hawaii’s second saint Oct. 21 when she is canonized in Rome, Law said.

"None of this changes the perception of Damien or Marianne," Law said. "It just tells a more complete story."

Ka ‘Ohana o Kalaupapa, a nonprofit group of patients, their relatives and others concerned about Kalaupapa’s legacy, is sponsoring workshops on Oahu and Maui later this month to share Law’s research to tell a different version of life in Kalaupapa before Damien learned about the plight of the patients in 1873.

Iolani Palace currently is exhibiting a display of early life in Kalaupapa.

Valerie Monson, who is helping to organize the workshops, said she especially hopes that Hawaii teachers attend so they will begin including the new perspectives in their classroom lessons about Kalaupapa.

"The history of Kalaupapa has traditionally been told almost exclusively through the use of English-language sources, even though hundreds of letters and petitions written in Hawaiian by the early residents of Kalaupapa and their family members have been preserved," Monson said.

"Consequently, the perspective of the estimated 8,000 individuals who personally experienced forced separation from their families and places of birth has been largely omitted from Kalaupapa’s history. … As a result, the history has been largely told from the Western perspective of shame rather than from the Hawaiian perspective of great love."