‘Toni Erdmann’ is a savage satire critiquing the ways of the world

SONY PICTURES CLASSICS

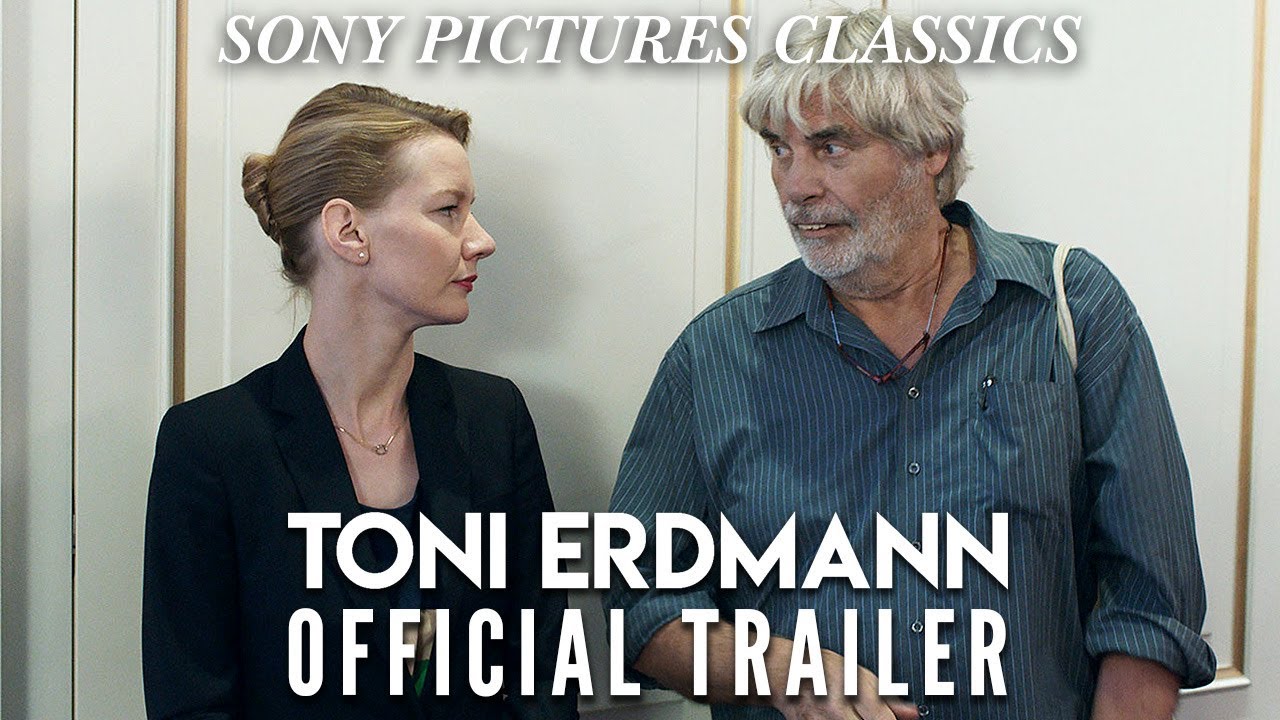

Peter Simonischek and Sandra Hueller star in the German comedy “Toni Erdmann.”

“Toni Erdmann”

***

(R, 2:42)

Early in “Toni Erdmann” — by a wide margin the funniest almost-three-hour German comedy you will ever see — there is a brief discussion, conducted in a sterile modern office building in Bucharest, about the meaning of the English word “performance.” For Anca (Ingrid Bisu), a young Romanian employed by a global consulting firm, it refers to the way she does her job and, more than that, her ability to obey the norms and protocols of the corporate workplace. Her boss, she explains, gives her “a lot of feedback,” which is clearly a euphemism.

That boss, a fearsomely serious executive named Ines (Sandra Hueller), happens to be the daughter of Winfried, the man Anca is talking with. It is already clear that Winfried (Peter Simonischek), a shambling, unshaven music teacher with a mop of gray hair and a prankish sense of humor, has ideas about public and professional behavior that would raise alarms in any human resources department. He carries a set of joke-shop fake teeth in his shirt pocket and has a habit of disrupting the routines of everyday life with absurd and outrageous improvisations. If for Anca and Ines performance is a synonym for conformity, for Winfried it’s the opposite. To perform — to act out, to pretend, to take on a new and unexpected personality — is above all to lodge an existential protest against the standardization of life.

“Toni Erdmann,” written and directed by Maren Ade, is its own kind of rebellion, a thrilling act of defiance against the toxicity of doing what is expected, on film, at work and out in the world. It is named for its improbable hero, the outrageous alter ego Winfried impersonates during his visit to Bucharest. Accessorizing those awful teeth with a stringy black wig, a baggy sharkskin suit and the kind of two-toned dress shirts favored by insecure business-class big shots, Erdmann shows up wherever he is likely to cause Ines the most embarrassment, variously claiming to be the German ambassador and a freelance management coach.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with top news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Ines isn’t fooled by the costume, of course, and it’s not always clear whether her colleagues believe Erdmann’s nonsense or are playing along with a joke they don’t quite get. Nor are Winfried’s intentions entirely legible, at least at first. Is he trying to humiliate his daughter, or to save her soul?

“It’s very complicated,” he sighs at one point, still in disguise, when Ines is out of earshot. And “Toni Erdmann,” proceeding in a perfectly straightforward manner, from one awkward, heartfelt, hilarious scene to the next, wraps itself around some of the thorniest complexities of contemporary reality.

It is, most simply but also most elusively, a sweet and thorny tale of father-daughter bonding with a finely honed edge of generational conflict, propelled by two extraordinarily natural, utterly fearless performances. Winfried, a shaggy baby boomer, has had the luxury of conflating irresponsibility with idealism. Amicably divorced from Ines’ mother, devoted to his own mother and his aging dog, he has settled into a permanent, pleasant state of not-quite-adulthood, in which he reserves the right not to take anything too seriously.

Ines enjoys no such luxury. Like many children of vaguely counterculture parents, she has rebelled by joining the establishment. Everything about her — her omnipresent cellphone, her crisply tailored blazers, her trim physique and curt manner — can seem like a calculated rebuke to her anarchic dad. She dares him to judge her, and when he does, she strikes back, dismissing his naive, pious criticisms of her turbo-capitalist lifestyle. Navigating deals and presentations, managing difficult clients and sexist colleagues, she is living in the real world and fighting for a place in it.

Ade, who at 40 is closer to being Ines’ peer than Winfried’s, is sympathetic to both of them, but not exactly neutral. “Toni Erdmann” may look like farce — and it does achieve heights of pure, giddy silliness of a kind rarely seen on the big screen these days — but it is driven by a savage satirical energy, a thoroughgoing critique of the way things are. The worst humiliations Ines suffers come not from anything outrageous her father does, but rather from the everyday piggishness of the men who belittle her work, thwart her ambitions or take her for granted.

She swallows their slights and tries to adjust her performance to their expectations, making herself miserable in ways that she can’t entirely recognize or acknowledge. She is also part of an enterprise, a system, that is spreading misery across the globe in the guise of opportunity, modernization and efficient business practices. “Toni Erdmann” sets its critical sights not only on the odd folkways of the executive class, but also on German arrogance within the European Union and the casual cruelty of international capitalism. Erdmann may be able to save Ines, but it’s not clear who will save Romania.

But maybe neither one really needs saving. This film’s generous, skeptical spirit is in any case more diagnostic than prescriptive. Like its hero, it wants to shake its audience, at least for the moment, out of habits of complacency and compromise, to alter our perceptions and renew our sense of what is possible. There are things you will look at differently after seeing “Toni Erdmann.” A short list might include petits fours, cheese graters, team-building exercises and a certain song immortalized by Whitney Houston. Also German comedies, Bulgarian costumes, Romanian hotels, fatherhood and the anxious, absurd state of the human race in the 21st century.